Summary of Episode

#43: Josh Cliffords sits down with Ethan to share his story founding FreeWater, an innovative advertising platform where companies pay to put their ads on spring water, and this water is then distributed for free. FreeWater places a focus on improving sustainability and promoting philanthropic efforts.

About the Guest:

Josh Cliffords is the founder and CEO of FreeWater, the world’s first free beverage company. Josh has founded numerous companies, but in 2018, he decided to tackle the world’s water crisis and hasn’t looked back. Josh’s ‘negatively-priced’ business model leverages advertising to make goods and services pay for themselves, and while he is currently focused on growing FreeWater, he has plans to continue expanding this business model into new industries.

Podcast Episode Notes

Combining free lemonade with baseball card sales [1:31]

The world’s first free beverage company [5:30]

Tackling the water crisis [6:31]

The negative business model — how can the product be free? [9:15]

The vision for a free supermarket [14:11]

Rethinking the traditional view that “capitalism is a zero sum game” [18:04]

Factors preventing big companies from adopting the negative business model [21:44]

The innovator’s dilemma [26:31]

Ads for everything … is this apocalyptical? [31:13]

Building a sharing economy [31:48]

How Josh developed the skills to build FreeWater [37:29]

Failing and pushing onwards [40:34]

TikTok success and constructing a zero dollar new acquisition cost [41:21]

It all starts with “the why.” Find a why that people care about [46:32]

Josh’s advice to new founders — go live in a new country where you can be happy, experience a new culture, and find an affordable living space [48:55]

Full Interview Transcript

Ethan: Hey everybody and welcome to the Startup Savant podcast. I’m your host Ethan, and this show is about the stories, challenges, and triumphs of fast-scaling startups and the founders who run them.

This week we are joined by Josh Cliffords, founder of FreeWater, a startup that is on a mission to change the world by charging absolutely nothing for their products.

Josh is a truly interesting guy. He’s got some big ideas. And what he’s accomplished with FreeWater to this point is pretty darn impressive. The big thing I’ll point out before we jump in is Josh’s ability to think outside the box - and not let conventional or societal thought patterns get in his way.

Quick plug: If you’re looking for guides and tools to improve your startup, head over to startupsavant.com and don’t forget to subscribe to this podcast on whatever platform you’re listening from. Now let’s get into my conversation with Josh Cliffords.

Josh Cliffords: Yeah, thanks for having me. Really excited to be here.

Ethan: Awesome. I'm going to cut the nonsense puns right now, but we're going to get into a really awesome story that you were just telling us before we started the podcast and I probably shouldn't have let you go on as far as you did because it was just awesome. Can you tell us the story of the lemonade stand?

Josh Cliffords: Yeah, so I grew up in Los Angeles, California. We had a lemon tree. I was that kid who was selling lemonade whenever I could. I don't know what happened, but one day I was like, "What would happen if I made a sign that said free lemonade?" Even though it was like 25 cents back in those days per cup, the free sign, people were just lining up around the block. I couldn't squeeze the lemons fast enough, literally. I'm like, "Oh no, what am I going to do?" But I was that spoiled middle class kid. I had a really good baseball, basketball and football card collection back in those days.

I grabbed the paper buckets, like the books that had the prices back in those days and the price guides. I brought all the cards out. People would come in for the free lemonade, and that was my first freemium model. I would sell them the baseball, basketball, football cards. I had a lot of good cards like Pippen rookies, Stockton rookie, Michael Jordan's second year card, you name it. I sold it and I brought in more than 1,500 bucks that weekend.

Ethan: Nice.

Josh Cliffords: My parents thought that I had stolen the money. The neighbors were like, "No. He somehow did that." And so not long afterwards, I was watching a show called Family Matters with Steve Urkel, and in one of these episodes, he invented a time machine and the neighbor stole it and invested in Microsoft and Disney and became the richest person on earth, and I was like, "Wait a minute." I was looking in the living room, that was our first computer, AOL version 1.0 with the whole dial up thing. I was like, "Everyone's going to want to have one of these one day." I bugged my parents for six months until they let me parlay that $1,500 in a Microsoft stock, and that was the mid '90s in the peak of the tech bubble growing. It kept splitting and going up and splitting and going up and splitting. By the time I was in the ninth grade, it was worth like 36K. Then the tech wreck burst, and then I sold it when I was 18 and started traveling the world with that money.

Ethan: That's such an awesome story and good on your parents for not being like, "Okay, let's take the win here, let's sell it early." That sounds like you really got to benefit.

Josh Cliffords: Well, they tried, they tried. They were like, sell half, let half ride. I was in the ninth grade. I'm like, "Listen, if Jim Cramer and all these people are wrong, because at that time, like clockwork, go to 150 split and go back, go to 150 split. I'm like, if it goes to 150 splits and goes up to 100 one more time, I'm going to have 300 grand by the time I start the 10th grade."

Ethan: Heck, yeah.

Josh Cliffords: I would probably still do the same thing today. The logic was there, but when you're gambling, [redacted] happens.

Ethan: Well, and so if you would've even taken a different gamble, I mean, I hate to even ask, but what would that have been worth today if you've just kept it going?

Josh Cliffords: A million bucks, close to it. But that was the only time I was a day trader my whole life. When I was 11, 12, I was making daily trades.

Ethan: That's awesome. Let me ask you this. What's worth more, a million bucks or all that world travel you got to do for free, basically?

Josh Cliffords: That was just the beginning of traveling the world. I mean, you could do a lot of traveling with a million bucks, but I guess those experiences were priceless. But some people say, "Oh, I have to say that because you're upset that you don't have that million bucks." But now, I'm 37, so I have 27 years of stock market experience. That's pretty cool.

Ethan: Heck yeah. That's awesome. All right, thanks for telling us that story. I love it. I love the young entrepreneur mindset and just seeing what can come out of that. Let's get into the feature of today. Tell us what is FreeWater?

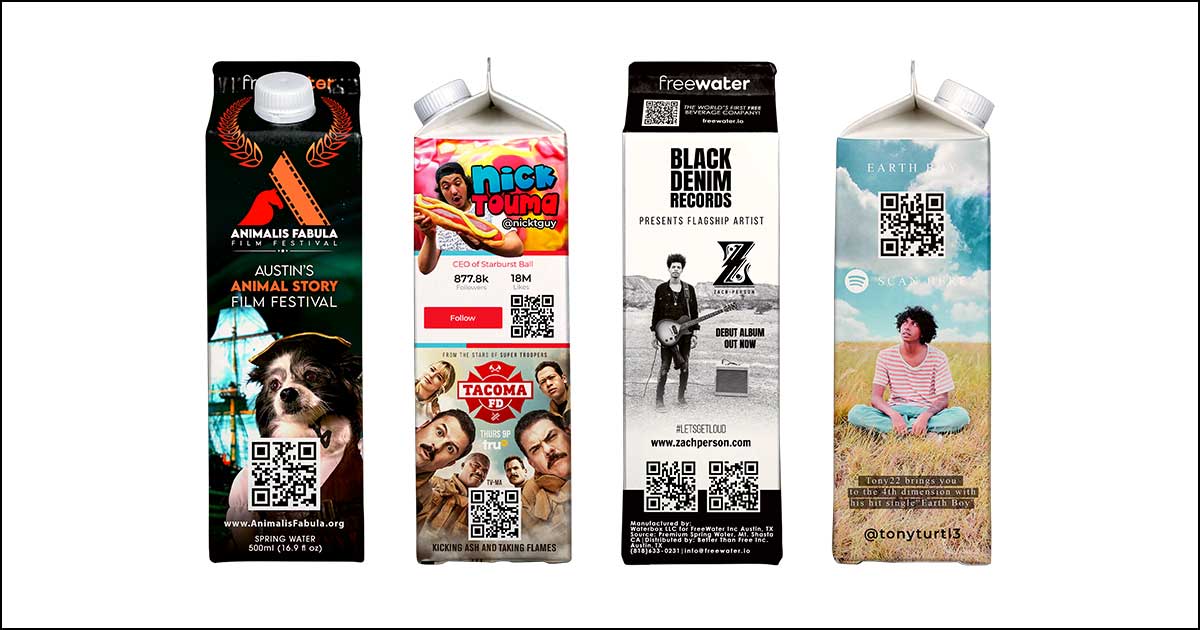

Josh Cliffords: FreeWater is the world's first free beverage company and our spring water and aluminum bottles and paper cartons is free because the packaging is the ad space. That's the catch. It's a new type of media and eCommerce platform. The most unique thing about our products are they're negatively priced. It's free, it donates to charity and we still make money. This isn't just possible, it's more profitable than selling groceries today. I say groceries because FreeWater is just the first product of our negatively priced supermarkets or Amazon if you will. We're just getting the permits now to launch free beer in the state of Texas next. Then we're going to be scaling free beer that donates to charity, 21 or over, of course, and then one product at a time. Before you know it, bam, free supermarket.

Ethan: I've never been more sad to not live in Texas than right now. We're going to get into this free supermarket and this Amazon 2.0 as you've called it in the past. But first, what's the problem that you're solving with FreeWater?

Josh Cliffords: With all free groceries that donate to charity, we're ending global famine here. If you ask the UN or the United States what it would cost to end global famine permanently, they don't even have a number for that. But their number to temporarily solve it is way over the top, and that's the type of number you get when governments spend $50 on a nail and a thousand dollars on a hammer. But when I calculated it responsibly, not wasted that way, to end the global water crisis permanently is $10 billion or less. Any government could solve it in a second. They choose not to. I personally believe it's because these are publicly traded commodities, water, pork bellies, you name it.

The goal with FreeWater is to end the global water crisis permanently. We call it the 10% rule. The average American spends five or 600 bucks a year on bottled water and those people drink up to six bottles a day. Our goal is just to give 10% of Americans three free beverages a day starting with water. Each of these donate a minimum of 10 cents towards ending the global water crisis. When we hit that 10% mark with FreeWater, we're donating $3.4 billion a year to charity, that single product. In a few years of achieving that 10% milestone, we've ended the global water crisis permanently. That means building water wells and water systems for 800 million plus people around the world without a penny of tax dollars.

Ethan: That's awesome. That's such a huge goal and I love that this free product essentially is the thing that is going to solve this thing that it seems like money hasn't been able to solve in the past. Can you tell us where you're at with that massive goal? I mean, if there's a percentage number to put on it, I mean ...

Josh Cliffords: Oh, we are not even scratching it.

Ethan: Got it.

Josh Cliffords: We launched this year, we built two water wells in Africa this year.

Ethan: Wow.

Josh Cliffords: Whatever you want to call it. We saved a few thousand lives. Next year, our goal is a hundred, then the year after that, a thousand, then 10,000, then so on and so forth. But yeah, usually socially conscious products cost more like TOMS shoes. You pay more for that pair of shoes and they give a pair of shoes or usually the healthy product or the shirt made out of hemp or whatever it is. If you're trying to do right by the environment or health, usually they tax you a lot more for that. We believe it's important for that highest quality and greenest products to be the cheapest, and so that's why we went negative. Now, donating to charity is as simple as saving money on your groceries, one product at a time.

Ethan: That makes sense to me. When we talk about making sense though, we need to talk about this business model and the fact that essentially it can be free because of the ad space that is on the product itself. This product that you have or these two products that you have so far being a can of water and a carton of water, obviously, they are the size that you would normally think of. They're about 16 ounces each. It's the size of a bottle of water and they're in the places that you would normally find bottles of water. But the other side of this product, aside from giving it away for free, is that you have to be able to sell the ad space on the product itself. How are you convincing advertisers that this is a solid medium for them to share the message that they want to get across?

Josh Cliffords: Okay, great question. Before I answer that question, I just want to point out, I hate advertising with a passion, and so we wanted to take an industry that I don't think is really positive and put a positive twist on it. We also created ways to make all groceries free in the future with no ads. What you can expect is for us to one day disrupt this current model with that. Now, talking about where we're at today, advertisers come to us because we created a system where they learn about us and we can't even keep up with the inbound advertising inquiries. But the future for us is all outbound B2B. In the short term, we've got hundreds of billions of dollars in opportunities just sitting on the table waiting to be approached. Right now, the problem is it's a good problem to have.

We get so much traffic on our website that if you filled out a get-a-quote form on our website, it would currently take 10 days for us to get back to you. That's horrible. Now, we're putting salespeople in place to get that down to 24 hours or less. But when we start approaching these outbound opportunities, there are many verticals where we have zero competition because we invented all these verticals. We're ideally going to start with the verticals where we have zero competition. You can't do water billboards, Google, none of them play in these fields, and a dollar made is a dollar made. We're going to bring in hundreds of millions of dollars in these verticals, keep adding technology to our platform. Then when we're bigger, wiser, and stronger in the future, then we're going to beat Facebook, Google, and TikTok on their own home court advantage.

Ethan: What does that look like? I mean, if you're moving away from ads and you're taking the revenue out from under those highly established companies, what does that look like?

Josh Cliffords: Again, we're going to focus on the verticals where you have no competition ideally at first. It's not traditional advertising, it's just new forms of communication. It's not just advertising. I'll give you an example. If we were in business when the pandemic started, we would've sold hundreds of millions to the CDC, it would've said, wash your hands, social distance, scan this if you get sick, track the virus in your neighborhood. Then later it would've been, "Hey, learn more about the vaccine, make an appointment, blah, blah, blah, blah." It's not just traditional marketing, which is on the table here.

We've got military use cases, humanitarian aid use cases, Department of Defense use cases. We could prevent companies from being hacked. There's just so many out of the box solutions that are on the table and there's so much money on the table in those verticals. We're going to attack those first, and then later as we build more and more tech to this platform, launch our free vending machines, launch the media and eCommerce platform officially, and a new type of bidding algorithms that's 10 times more advanced than what Facebook and Google and TikTok use, then we're going to own everything that they do best to in the most humble and conservative way possible.

Ethan: Gotcha. Okay. I feel like we could talk for days about the future of all the things that could be done, but I want to get back into what's going on today. You were telling us about free supermarket being kind of the next iteration of FreeWater. Can you tell us more about the free supermarket?

Josh Cliffords: Sure. Let's just talk about the current industry right now. Unfortunately, in the United States, 30% of all groceries go straight from the supermarket shelf and into the trash because it's too expensive.

Ethan: 30%?

Josh Cliffords: 30%, so 30% of all fish, anything you see in that market, steaks, milk, bread, 30%. Now, that means when we scale free supermarkets across the US and not just ours, other people will copy and do their own version of it. We're going to cut USA food waste by 60, 70 billion a year. But it's much more than that because maybe that piece of fish was caught in Alaska. It's all the fuel spent to get that, and guess what? That fish is wrapped in plastic. Well, where did that come from? That came from oil in the Middle East that was put on a tanker, shipped to China. China's the largest maker of these little plastic pellets.

Then those plastic pellets came to Argentina, they smelted it into a wrap, they wrapped that fish up and then it stopped 10 times on this really broken supply chain we currently used before it ends up in your local supermarket just to have 30% of it go straight into the trash. The future is free. The future is trying to never ship. The future is local. Free supermarkets across the board right there, we're talking 60, 70 billion in savings. But it's much more than that due to the broken supply chain that we have. It's just going to have a windfall effect for the environment for each family in the United States. How much will the average American family save when all of their groceries, computers, T-shirts or everything are free? We're talking five to $25,000 a year in savings that they'll spend somewhere else, maybe on our platform, but they don't have to.

There's just a lot of good there. Now, these aren't free, these are negatively priced. Every product that we're talking about will donate to a different charitable cause. Let's say if Apple's donated towards solving children's cancer, like everyone wants to prevent that from happening. Well, when you get 10% of Americans, one Apple a day, 10 cents per Apple, blah, blah, blah, blah, it's more than a billion dollars in donations to that cause. The real vision as this unfolds, every free product or negatively priced product is donating to a different charitable cause. These actually are not products. This is PR as a service because we're also never going to pay sales tax. You don't pay sales tax and marketing services. That's just another advantage that we have because products are free or negatively priced or services, whatever you want to call them, there's new ways to manufacture and distribute that are not possible when things cost money.

The interesting phenomenon is if you combine the manufacturing and distribution of Coke, Pepsi, Nestle, Walmart, Target, Costco, and Amazon and Levi's jeans and Apple, collectively, their infrastructures couldn't do what we're going to build out because they all built them incorrectly, or not incorrectly, but for world where things cost money. We're building out a new type of infrastructure that allows us to go direct to the consumer in the future and 95% less channels. It's that combination of these other forms of revenue that people weren't collecting due to social norms or just whatever and then the cost savings on the backend. You bake that together in a cool pie that's really philanthropic but more profitable than selling goods today.

Ethan: Where do the products originate from? Where do they come from? Not where specifically, but the person who's fishing those salmon from Alaska and the people that are growing the apples on the orchards, how are they being compensated in this system?

Josh Cliffords: The same or more than they're being compensated today. Have you ever heard the expression capitalism's a zero-sum game?

Ethan: I have heard that expression, yes.

Josh Cliffords: That means there's one winner and many losers, at least one loser. But we call this the giving economy, which means we earn a profit while distributing products and services at a negative value proposition. For us, it's five winners versus one winner and many losers. In the giving economy, the audience, they get high quality products and services for free, actually negatively priced. The advertiser gets their targeted desired person. We donate to charity. We're the middle man so we take a slice of the pie and the manufacturers get their asking price. It doesn't matter if they distribute the iPhone to us and we distribute that at a negative value, or if they sell it through traditional capitalism, Apple gets their asking price. And so whether it's the apple orchard or the potato farmer or whatever, however you have it, they're getting what they're asking.

Ethan: Is this still the ad supported model or is this a new revenue model that's supporting the...

Josh Cliffords: Either or.

Ethan: ... money that goes to...

Josh Cliffords: Either or.

Ethan: Okay.

Josh Cliffords: The reason why one day we're going to be able to give free groceries with no ads is we're just going to be making so much money off of free electricity that we're going to why wouldn't? I mean, we're here to help people, it's only so much money someone could spend and it makes me uncomfortable how profitable this is, to be honest.

Ethan: Then at that point, are you just donating more to charity? If you want to take those profits and put them where you think that they're going to be most valuable, is that the answer?

Josh Cliffords: 1000%. Today, on the can it says, or on the box, we donate 10 cents per unit. Right now, we're averaging 15 or 16. We're only going more negative from here. Right now, our water depending on how you look at it, is 110, 115% off on the consumer side because free plus charity. As we build out this new manufacturing infrastructure in the coming years, now you're getting free local delivery and then the icing, like the cherry on top in the future, you're going to also get paid to eat the free stuff. When the dust settles, let's say 10 years from now or however long it takes, our products are going to be discounted somewhere between 150 and 175% off. But we still make more money than you could while selling these goods today. Coca-Cola can't make a thousand dollars from a can of Coke, but in the future, we can earn more than a $1,000 from a free banana or free slice of pizza.

Ethan: What are the changes that need to happen in either our supply chain or our economy or in just the way that people think? What are the changes that need to take place in order to make this a reality?

Josh Cliffords: I mean, it already is a reality and we're growing it every single day and people from around the world are copying and we welcome that, and we want Coke, Pepsi, Nestle, and Amazon to copy. What are they going to do? They're going to put us out of business by opening a better free supermarket that donates more money to charity. We'd save 50 million lives a year if that happened. Okay, our products are negatively priced and we might be the first people in the world to do that, but we're more the first people to identify this new type of economy. This phenomenon already exists in software.

Back in the day, I'm 37, we used to pay for video games and consoles and then Fortnite and all these, now it's free. But now, the video games are negatively priced because those free video games will pay you to play them by mining crypto and minting NFTs. Technically Facebook would be negatively priced, it's free, but they donate so little to charity that no one looks at them as being negative, because most people don't look at them in a positive light. But you've got Ecosia, it's a German search engine, it's free, but 70 or 80% of their revenue goes towards planting trees. That should be 170% off, and so these systems already exist in software. We just brought them to the physical world.

Ethan: Okay. Okay, that makes sense. You mentioned people copying you, these other companies copying you. That was a question that I had prepared: what's the moat of this business? What is stopping anybody else from taking this model and just doing it for themselves? It sounds like maybe the answer is not only is there not a moat, but we want to put up on a billboard to, hey, copy us, we want you to take this model. But the question that I have from that is, what is the possibility, then what is the case after that, that a company takes this free model and then doesn't donate the percentage of anything to the charities? What happens if they use the good parts of this model and then don't move into the parts that don't feed the further ecosystem?

Josh Cliffords: Okay. That was four questions. I'm going to knock them out one at a time.

Ethan: You can hit them all however you want.

Josh Cliffords: Number one, we have more moats than any company in history, but I'll get it to that in a second. We want the world to copy. If Coke's CEO called right now, I would help them. Same thing with Amazon or any of them because we're trying to end global famine here. It's not a competition. If they put us out of business by opening a better free Amazon that donates more money to charity, we win, because our goal is to save these 50 million lives a year that are currently dying.

We believe in vain, but number two, the biggest companies in the world can't copy because we have so many moats. Moat number one, if Coke, Pepsi or Nestle or whatever, if Coca-Cola takes Coke off the can and copies us, their stock is going to plummet. Just like when Facebook's switched to Meta, because the market does not like insecurities here.

Number two, there's a lot of social norms that they're going to have to get past. If Pepsi asked Coke, "Can I advertise on your can?" They would say no way. But they should say yes because they would 100% their revenue. In this new paradigm, you grow faster by helping your biggest competitors. If you call on your competitors, we don't look at them anyone that way. If Coca-Cola put ads on every one of their trucks in the United States, they would bring in between 500 million and a billion dollars a year. Why aren't they doing that? I thought they're in business to make money, but apparently, they care more about their logo.

Ethan: Well, are they doing that? I mean, it is advertising. They're advertising their own product and therefore they're selling their own product and so they're not making the money via advertising, they're making the money via sales of their own product. I mean, unless I'm wrong there.

Josh Cliffords: But does it need to say Coke on every square inch of the can for you to know what a can of Coke tastes like?

Ethan: You are not wrong. Yeah, absolutely.

Josh Cliffords: We can't just say Coke on the lip of the can.

Ethan: Yep, they couldn't.

Josh Cliffords: Or the manufacturer's info, and so it's just different in this new paradigm when people know who you are already. Now, you should be converting your real estate into other uses that bring in revenue. The next moat is again, they all built their infrastructures incorrectly, including Amazon, Walmart, Target, you name it. For a world where things cost money. I'll explain this. When things cost money, traditionally, people have made mega factories and mega fulfillment centers, think Budweiser, think Coke, think Amazon, right? And so you ship things across a town, city, state, country or the world. The further you ship it, the worse it is for the environment, the more the end user pays, and that's the norm at the moment. But free and negatively priced product services encourage a decentralized microfactory model.

With Austin, for example, we're not going to have one mega FreeWater factory. We're going to have 20 micro factories each two to three times the size of a McDonald's. In that small footprint, we'll be manufacturing between 200 million in a billion beverages a year just under that one roof. Now, any micro beer brewery that you've visited or whatever, they could be manufacturing hundreds of millions of more beverages than they do, but they don't because they couldn't sell it or store it. But our products are free. It's a hot potato game, make it, distribute it. It's a different type of model. They're going to have to build out this entirely new type of infrastructure to compete. Also, Coke, Pepsi, you name it, they're one or two trick ponies, they fill it and they send it off and they never want to deal with it again.

But the greatest companies out there like Apple or Tesla or whatever, they own their entire supply chain under one roof and that enables them to make magic happen. And so is Coca-Cola going to, instead of being a one or two trick pony, are they now going to be a 10? Like tricks, 10 legs? They're just not going to want to do it. I've spoken to the head of innovation of some of the biggest beverage companies in the United States and they're like, "Josh, we're never going to do that because we're so old school, we're just not going to do it, period."

Ethan: Because that was going to be one of my next questions is why aren't they doing this already? In that sentence, what does old school mean? What is it just that like this is how we make money and we're not willing to change? Or is it that people aren't willing to change? What's the old school in that question?

Josh Cliffords: All the innovators' dilemma. Usually when you're making billions of dollars a year, you're not going to tinker with other things. Usually companies don't tinker on things until death is on their doorstep and then they try to put a new roof on during a rainstorm and it's already too late. The next moat is no one knew that any of this stuff was possible. Everythingfreesomething.com was available and I bought them in every language.

Ethan: Good.

Josh Cliffords: We own SEO, like free sushi, free tequila, free Mexican food, you name it, I own it. We own the internet, we own the real estate. They're just too far behind in their tech and their processes in ways and they're just too big and slow. If they're listening out there, Coke, Pepsi, Nestle, Amazon CEOs, just call us. We'll tell you all of the secrets. Start doing this today and let's end global famine together and you'll 100 x your revenue, so why not?

Ethan: Yeah, I think that's a bold statement, but it's also, if that is how it would work, then yeah, I mean, let's race to see who can fix the world first. Let's go fast. Let's do it.

Josh Cliffords: That's why we created this model to be negatively priced. Imagine the number line that you saw in junior high where it's like negative 10 zero positive 10. Anything that is one penny or more in the positive zone, you have a certain set of rules. It doesn't matter if it's the sharing economy, the Uber of something or the Coke or Pepsi or Levi's jeans of something. But now anything negative one penny over here has a different set of rules. Anything to the right of zero is a zero-sum game, McDonald's or whoever might cut down every tree in the rainforest just to grow a little bit more beef if their stock goes up like a percentage. But anything on the negative side, you designed your company completely differently because you got to be like, "Well, how am I going to make money distributing T-shirts that pay you to wear them?"

I'm going to have to go through the supply chain, identify everything that's there, because of folklore, it's just there, because copycats and no one asked why. Once you throw out all that crap, then you're like, okay, I got to make money somehow. So maybe you make a video player or whatever that makes ads. Now, you are negative. But the only way to go negative with water, for example, the only way to make this water negative is its free. But I have to either pay you directly or I have to donate to charity. Either directly pay cash in your pocket or donate to charity. There's no other way to add value beyond zero. As we keep pushing more and more negative and make more and more money, more people are going to try to compete with us in this negative zone, and then what are they doing? They're competing with us to treat the consumer better, to help local economies and to donate money to charity.

That's the sort of competition we want to be the catalyst for. Then your last question, "Well, what about the people who are going to copy but not donate to charity?" What I predict is you won't see Coke take their logo off the can for many years, but they're going to start putting ads here around it like Nike, Airbnb, whatever. What they're going to do is they're going to subsidize those cans by a few cents and they're going to donate, let's say, a nickel to whatever charity the CEO likes best. Let's say if it's like the American Cancer Society or whatever it is. But when you think about the economies of scale that those companies have, a nickel per unit, that's billions of dollars a year.

Ethan: Tons. Yeah.

Josh Cliffords: We love that. But what's going to happen is people are going to be like, "Well, wait a minute, those still cost money and look at these free or negatively priced ones." Eventually that friendly sense of Darwinism is going to drive them to get to zero and then drive them to go beyond zero. If they don't do it, they simply won't be able to compete because we're making Coca-Cola and every supermarket free, even if they don't want it to be. Because the second leg of our platform will be a TikTok and YouTube competitor. We're going to be paying you to watch those ads. If you want a Big Mac for free, you're going to watch X number of ads, boo, there's your Big Mac and so McDonald's is going to be negatively priced regardless. They might as well do it with us or do it on their own because it's all going to zero and beyond.

Ethan: I've seen this before and I'm not being facetious. This was an episode of Black Mirror, where the guy was totally in his room and he needed enough credits or whatever, so he had to watch ads and then when he fell asleep, they woke him up and he watched more ads. Is that what this is going to turn the world into?

Josh Cliffords: No, because economic systems drive human behavior and that was still a zero-sum game society. Bitcoin is Bitcoin, but Bitcoin will operate differently in capitalism or the sharing economy than it will in the giving economy. Again, we created ways to make all these things free with no ads in the future. We just had to bootstrap it this way to get off the ground. For us, what we're most worried about, yes and I love Black Mirror and that's a scary show, so thanks for bringing that up. If we don't stop the degradation to the environment as soon as humanly possible, we're all in a bad spot. If you look at what's going on in the world, it could be the start of World War III. That's also no bueno. What are a lot of those conflicts over oil? Well, guess what I already told you, free supermarkets is going to cut USA consumption down by that.

That's a lot of oil saved. That's a lot of, and so we're basically trying to save the environment, save the people's lives who are dying for no reason, kind of prevent these future wars over food and water. But in the meantime, we need to make water and all these commodities available for free before it's too late because it's a publicly traded commodity and it's already being sold at 2,000 times the price that they pay minimum. But guess what happens in countries, the most water insecure countries on earth, people are paying half of their paycheck to drink water.

What's going on in the US right now? Lakes and things are drying up. No one in the government is making good suggestions like, "Oh, we're going to make a pipeline from Canada." But no one's saying water desalination on the coast of California. No one's saying to collect the fog, so but why? Because who owns the government? The lobbyists? Who owns the lobbyists? The corporations. We believe by adding a new sense of friendly Darwinism, lighting a fire under the corporations butts, they're going to change. By getting Coke, Pepsi, Nestle, Amazon, Walmart, whoever, Levi's jeans to change, then their lobbyists are going to have different asks

and then the government's going to pass different types of legislation. But it's got to start with the companies, not the government.

Ethan: Maybe this is a question that doesn't make sense and if that's the case, then you can just tell me or maybe it does make sense but it's just wrong. Is there a future that this brings on where money no longer is the technical store of value? Does the idea of having paper dollars or even dollars in a bank account break down under this new way of operating the world?

Josh Cliffords: It won't because unfortunately money is a main driver for many people. I think the questions we need to ask are, if you believe in self-driving cars like we do, we order 25 cyber trucks that will drive themselves.

Ethan: Nice.

Josh Cliffords: By the way, those trucks are going to cost us zero because we're going to put ads on the trucks and that's going to pay for all of our fleets. But if you believe in a world with self-driving cars, robots, AI, five to 10 years from now, we're all going to be out of the job. Being in the United States, are we going to have a universal basic income? I doubt it. It's kind of un-American, but we're in too big of debt. Companies like this, movements like this, when you have all of your products for free or negative, compensation for getting that free laptop or free pizza will be important.

The issue we have is there's just a bunch of tech being launched right now and it's going to really widen the gap that much more between the 1% and everyone else, because in the future, your net worth is going to be based on how many robots you own. If I own one robot, you own a hundred robots, we both have pizza places and someone else has zero robots, we're going to be a hundred times more efficient than the people at zero robots. You're going to be a million times more efficient than us. But what about the Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos of the world, who've got millions of robots and their robots are capable of building other robots that are better?

We're trying to try to change that, even the Elon Musks of the world, we want them to be more for humanity to do more with what they've got. The only way we feel like we could force their hand is by giving him a sense of competition, because we're going to make Tesla's free too. If he doesn't want to make his model three free, guess what? We're going to do that as well. Eventually, they're just going to do it because they have to.

Ethan: Have you heard the story of the factory of the future? The factory of the future has two employees. The employees are one person, or excuse me, one dog that is there to prevent anyone from touching the machines and one person who is there to feed the dog. Have you heard that story?

Josh Cliffords: I haven't, but it makes total sense. It's spot on.

Ethan: All right, let's move out of the future for a second and move back into the past, your past specifically. Now, you said you hate ad sales, which rock on because ads can sometimes feel gross and then ads sometimes are good. I'm not here to be the judge on that. But do you personally have any history in ad sales or bottling or CPG sourcing, anything that FreeWater is currently working on?

Josh Cliffords: Zero.

Ethan: All right. How are you bringing that knowledge into the company? Because I don't just assume that the water is floating on a magical cloud into the bottles currently, so how did you get that knowledge into the company?

Josh Cliffords: Hard work is the only answer. For my 30th birthday, I went on a trip around the world. My goal was 100 countries in four years and I was a quarter of the way done with that almost. I was in Rome for five minutes and I was really moved by the story of two Nigerian refugees. Their story was so sad. I canceled my trip around the world and made a non-profit organization called Save the Refugees in Eastern Europe. We helped more than 10,000 refugees. Speaking to those people, that's when my eyes were open to what's going on. Because 20 or 25% of them said they left their country because they didn't have water, food, or medicine. Then I was like, "Whoa, this is a huge issue." I met my wife, kind of forgot about these things, we were semi-retired living on the beach in the small country of Montenegro.

Our rent was 300 bucks a month, so it would be easy to be retired there and started remembering all those stories. I wanted to just say, "Hey, can I have a beer and sit on the beach and solve these things?" Within a few hours I created a handful of processes that haven't changed today. When I created these things, I realized, wait a minute, everything that's currently sold at a Costco, everything from computers to whatever, I could make free or even negative, still make money. First thing I did was like, "Oh, no way. No way." I don't want to rock that many boats. I don't want to disrupt all these industries. That sounds dangerous and uncomfortable. But most importantly, at those times I didn't know how to type or use a computer at 32.

Ethan: How is that possible? How did you do that?

Josh Cliffords: I graduated high school in '03 and I was a jock. I just played sports and I never… like my biggest phobia was computers. I was like, "How am I going to be the founder of this next great tech company if I can't even type some?" It's dangerous, I don't want to do it. I don't want to rock the boats, I don't want to be uncomfortable, I'm not going to do this. Then 90 days later, I felt so guilty because I was like, "We're going to save millions of lives and you're not going to do it because you don't want to be uncomfortable that you're scared that some of the biggest companies in the world could retaliate or whatever." From that guilt, I bought a laptop, taught myself how to type. At that time, Word docs and PowerPoints were like JavaScript or Python for me today. Basically for five years, I started at 8:00 AM and I ended at 1:00 AM seven days a week, and that's how I covered that much ground. When you work 100 hours plus every week, you could do anything.

Ethan: You really are just brute forcing this knowledge acquisition?

Josh Cliffords: 1000%. I failed a million times. You have no idea how many doors were slammed in my face the first 36 months. It's not possible. It's snake oil, you can't make it free, let alone negative. But I just felt so guilty, I just had to keep pushing. I still feel guilt because I know when just 10% of Americans eat our future free groceries and use our future free products as a service, as a marketing service, we're going to save a 100,000 lives a day. Thinking about the 100,000 people that are going to die today, just because I'm not saving Americans money, that bothers me and that bother or guilt or whatever you want to call it, that forces me to get up every day and do this.

Ethan: All right. I want to pivot into something that FreeWater is doing a really, really good job of, and that is your own marketing, specifically TikTok. On FreeWaters account, you guys have more than 600,000 followers. Your biggest videos have tens of millions of views. On average each video gets, I don't know, 40,000 videos or 40,000 views. I didn't do the math, it's just, that's what it looked like. First off, congratulations for being famous. How does that limelight feel?

Josh Cliffords: I wish we could do without it. I don't like being in the light, but we've created a system where we have $0 new customer acquisition cost. Because if I hand you a FreeWater, you're sold for the rest of your life. You want free water, soda, beer, pizza, puppies, anything. But the phenomenon is if you see a video of somebody getting something for free, you're equally as sold. It's our job to give away free products. We record a fraction of those interactions. We post them.

Sometimes they only get three or four or 5,000 views, sometimes they get 30 million views. Those people see that. The majority of those people are like, "I want free stuff and I'll support you. I'll sign up on the website, I'll wait for a later date." But then a fraction of those people are like, "Oh, I want to advertise to those people, or I want to invest or I want to join your company."

We had a video two or three weeks ago and I think it got 20 million views just on TikTok, but we guesstimate 50 million views on all platforms in the first three days that brought 60,000 people to our website in just 24 hours. Right now, we use it just as a bat signal and it's a movement. We're not a company, it's a movement, so people see that and then they share, they support. Right now we have 780,000 followers across all platforms. It's almost like we have 780,000 decentralized teammates rooting for us, and that makes everything easier.

Ethan: I know it's really difficult to take one video and understand “why was it this video that went crazy and got so many views?” But you all have a ton of videos and a lot of them are getting a lot of views. I think that that type of information is more legible. You can really look at the patterns and the things in the video and how you posted it and all these different things that go along with that video. Are you finding anything that is consistently driving more reach and better results with your TikTok videos?

Josh Cliffords: Yes and no. I'm refining it constantly. Right now, we have a major video every quarter, what I mean a major video, like a major, major video. Some of them, they're indistinguishable. Was it the sound we used, the time we posted it? Who the heck knows? Other ones, it's obvious.

Sometimes we'll spell something incorrectly on purpose in the video and then a bunch of people will then correct us in the comments. You spelled that wrong and then that pushes it. But what we're going to start doing is we're going to start getting one of those major videos every month, then every week, then every day, then a few a day. Right now, we're the content creators, but we're going to turn a corner very soon as we start ramping up because today we're the ones filming it. But once we get the product distributed from local supermarkets, from our free vending machines direct to your doorstep, then people are going to just make the videos for us because they all are behind what we're doing.

Then we get to just cherry pick those best videos and then repost them. As we start ramping up, then I could take less and less time and accomplish the same or more out of the social media and then still scale this. We haven't spent a penny on advertising in 14 months. I used to spend money on Facebook, Google and YouTube ads and one 50,000 view video on TikTok showed me that a 50,000 view video equated to spending eight or 10 grand on Facebook, Google, or YouTube ads. I'm never going to go back to spending on that ever again, why would we?

Ethan: What's creating the success? I mean, is it just the sheer number of videos that are being uploaded? Is it something about the people in the videos? I mean, what is it that is drawing so many eyeballs that people seem to be interested in seeing? I'm asking for the other founders out there who want to be as successful, more successful, near as successful on TikTok for their own companies.

Josh Cliffords: It starts with the why. Usually, when people get a FreeWater from us, they're like, "Well, water should be free anyways." These people believe what we believe that water, food and medicine should be free, accessible to everyone and accomplished in the most eco-friendly manner possible. If there was no why there, then we would have zero success, period. I would say we'd have 6,000 followers instead of 600,000 followers. Any founder that wants to duplicate it, they have to have a why that people care about and they should probably have that anyways before they start their company, because startup life is really rough, but it starts with the why. Then now, a lot of food or beverage companies, if you look at their social media, it's like, "Oh, I drank this energy drink and it tastes amazing and I feel great," but we're spring water.

I mean, water's water, most products are just, they're not... Like its water, everyone knows what water tastes like. More important than having someone take a sip like, "Ah, this is the best water in the world." It's their reaction to the fact that it's free, donates to charity, and not in a plastic bottle. Those reactions are for us what scales. Because we had one video recently with this angry European guy who's just like, "It can't possibly work. Who pays the spring? Who pays for the aluminum? Who pays for the..." That video alone up by some of the biggest venture capitalists and crypto people in the world, they posted it on Twitter and LinkedIn. They got millions of views, they reposted it like this guy did more due diligence on a free bottle of water than most VCs did on tech companies in 2022.

Ethan: He did ask a lot of questions. He really did.

Josh Cliffords: It's the surprise on their face. People are always asking and like, "At least 10% of the videos, well, what's the catch?" Then we tell them it's free because it's paid for by ads, we donate to charity and they're just blown away, and so it's that interaction that scales.

Ethan: I think that's a really excellent answer. All right, so we're moving close to the end here and I've got one more question for you before we wrap up. That is, what is your number one piece of advice for early stage entrepreneurs?

Josh Cliffords: I'm going to give them an odd piece of advice that most people wouldn't, and it's leave the United States or whatever country you're in and go live in a more affordable country. Like go live on the beach in Thailand, Bali, Eastern Europe, Costa Rica, whatever excites you. When I invented this, it took me more than two years to invent all this stuff. Well, when I was living in Eastern Europe with my wife, our rent was between 150 and 350 a month for fully furnished apartments with all utilities and everything paid for. That extends your runway infinitely. Then when you're living abroad and in a different country, culture, language, food, you are surrounded by unique experiences. It's exciting. It's fun. You're not worried about your rent or anything. You can't spend all of your money.

From that feeling of happiness, excitement, unlimited runway is when you might recreate the next wheel versus a lot of founders will be like, "Oh, I'm going to quit my job at Facebook or Google or wherever and I've got six months before I run out of money and I got to raise venture capital. I got to recreate the wheel, I got to..." That is not, that's too much pressure to innovate in my opinion. It's too much pain to sit there and really invent something well, because most founders create something that's just incrementally better and then you don't have a moat. You shouldn't make something that's just incrementally better. It should be a 100X better.

Ethan: Right.

Josh Cliffords: Then they can't copy even if they want to just like with us, but we welcome it anyways. Give yourself unlimited runway. Go to a place that's much cheaper than where you live. There's almost always a cheaper country than yours, no matter where you're from. Then just give yourself time to invent. Take all the time in the world. Make sure that the why is so important that you just can't quit even if you wanted to. That's what happened to me, because I would feel too guilty if I did. If you knock all those things out, the why is something you're so passionate about. You give yourself unlimited runway and you make sure that it's not incrementally better, maybe you just created the next Tesla or the next water that pays you to drink it.

Ethan:

Alright everyone, thanks for tuning into today’s show! We’re so glad you joined us!

Quick note: check out our YouTube channel, where you’ll find clips, full-length podcast videos, and more excellent startup content.

If you liked this episode, it would be awesome if you could share it with a friend! And if you really liked it, head over to Apple Podcasts and leave us a rating or review. Those two things are what grows the show, and allows us to keep having these awesome conversations.

Thanks, y’all.

Tell Us Your Startup Story

Are you a startup founder and want to share your entrepreneurial journey with our readers? Click below to contact us today!

More on FreeWater

Founder of Social Startup FreeWater Shares Their Top Insights

Josh Cliffords, founder of social startup FreeWater, shared valuable insights during our interview that will inspire and motivate aspiring entrepreneurs.

Here’s How You Can Support Social Startup FreeWater

We asked Josh Cliffords, founder of FreeWater, to share the most impactful ways to support their startup, and this is what they had to say.

Solving the Global Water and Food Crises Once and for All

FreeWater aims to solve the world’s water and food crises for a fraction of what it would cost governments or nongovernmental organizations to do.